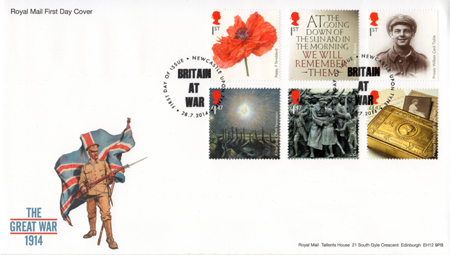

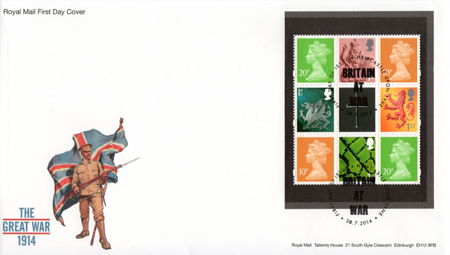

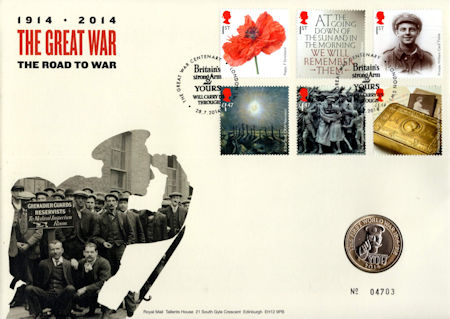

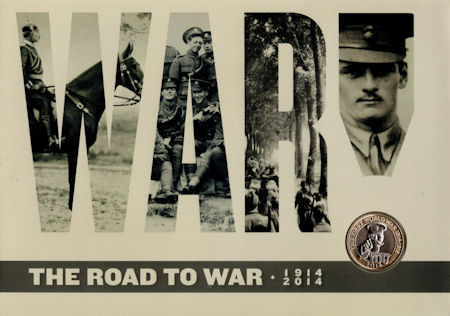

The Great War - 1914

The First World War was an event without precedent in history and touched every household in Britain, eitherdirectly (with family members killed, injured or lost in action) or through the immense social changes it

triggered. The centenary of this conflict is being marked with a series of 30 stamps to be

released over the next five years. Each year of the war will be commemorated by a set of six stamps, exploring six visual and thematic strands: poppy, poetry, portraits, war art, memorials and artefacts.

2014 (July 28 2014)

Commemorative

Designed by Hat-trick Design

Size 35mm (h) x 35mm (v)

Printed by International Security Printers

Print Process Lithography

Perforations 14.5 x 14.5

Stamps

Poppy

1stImage preview by Royal Mail

The poppy quickly became symbolic of the war. It was previously associated with the powerful effects of opium and detested by farmers as a stubborn weed, but its tendency to spring up on disturbed earth made it a common sight among the broken ground of shell-torn battlefields. The poppy’s deep red colour seemed to evoke the blood of wounded men, while the flower’s delicate petals might hint at the fragility of life itself. In this specially commissioned painting, artist Fiona Strickland captures the fine texture and translucency of a poppy’s petals.

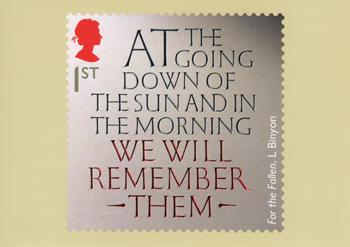

War Poetry

1stPhosphor All Over

Image preview by Royal Mail

In 1914, Laurence Binyon was a senior curator at the British Museum and an authority on East Asian art. Born in 1869, he was too old to enlist at the outbreak of war. He had been a published poet since the age of 16, and on 21 September 1914, The Times printed his seven-stanza poem ‘For the Fallen’. At this time, the British Expeditionary Force was in retreat, having suffered heavy casualties at the Battle of Mons. Binyon’s poem is very well known today, being used across the world in the ‘Ode of Remembrance’.

Portrait

1stImage preview by Royal Mail

Private William Cecil Tickle enlisted during the height of the recruiting rush on 7 September 1914. Despite being underage, he managed to join the 9th Battalion, Essex Regiment. After a period of arduous training, the battalion was deployed to France and on the third day of the Battle of the Somme attacked near the village of Ovillers. The troops were hit by machine-gun fire from three sides and suffered heavy casualties. Among the dead was Private Tickle. Having no known grave, he is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme in France.

War Art

£1.47Phosphor All Over

Image preview by Royal Mail

Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson was born in London in 1889. A leading exponent of Futurism, he went to France and Flanders as a Red Cross orderly, later joining the Royal Army Medical Corps. After being invalided out of the Army, he secured a commission as an official war artist. One of Nevinson’s official works, Paths of Glory, showing two dead British soldiers lying amid mud and barbed wire, was controversially censored. In A Star Shell, Nevinson depicts the weird, unearthly light of an illuminating artillery flare. The shell’s harsh glow reveals a strange landscape of broken ground and barbed wire and captures the disorienting alien nature of the battlefield.

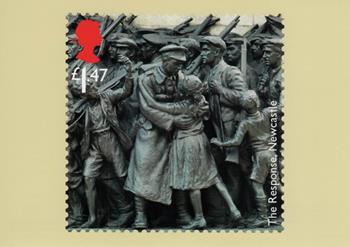

Memorial

£1.47Image preview by Royal Mail

The Response, otherwise known as the Renwick Memorial, was inaugurated in Newcastle in July 1923. A spectacular sculpture by William Goscombe John depicts the volunteers of the Northumberland Fusiliers marching to the station on their way to France. Led by drummers and heralded by the figure of Victory, the men walk resolutely as two sweethearts part for perhaps the last time. Field Marshal Lord Kitchener’s call to arms in September 1914 met with an instant and overwhelming response. While the pre-war British Army needed 30,000 recruits a year, at the peak of the recruiting rush this number enlisted in a single day. By the end of 1915, 2.5 million had volunteered.

Artefact

£1.47Image preview by Royal Mail

On 15 October 1914, Princess Mary launched her Christmas Gift Fund. In a public letter, she wrote, “I want you now to help me send a Christmas present from the whole nation to every sailor afloat and every soldier at the front.” Her appeal was met with an enthusiastic response, eventually raising over £162,000. On Christmas Day 1914 alone, 426,724 gifts were distributed to British service personnel. Each included writing materials, a Christmas card and a photograph of the Princess, and most contained tobacco and cigarettes, all enclosed in an embossed brass box. Many boxes survived, becoming distinctive mementoes of the war’s first Christmas.

PHQ Cards

RM Code AQ211